The Rohingya people are considered “stateless” under international law. But what does the term actually mean?

Medecines Sans Fronteries humanitarian affairs coordinator, Gina Bark explains the concept of statelessness and what that means to an individual.

A stateless person is someone who is not recognised as a citizen under the laws of any country, which means, simply, that they hold no nationality. It means you do not belong to any country and you're not seen as a national of any country. You're provided absolutely no legal protection and you're denied basic rights. You have no entitlement to any right that is associated with citizenship. That includes almost all basic and daily activities, rights to education, healthcare, employment, housing, even marriage, freedom of movement and political participation.

If you think a bit about it in your own lives, these are the things that we take for granted on a daily basis. They're the basics of living. Imagine not being able to send your kids to school. You can't open a bank account. You have no right to apply or the ability to work, no ability to seek healthcare, no way to rent or own a home. No right to even get legally married and no right to vote.

THE ROHINGYA AND STATELESSNESS

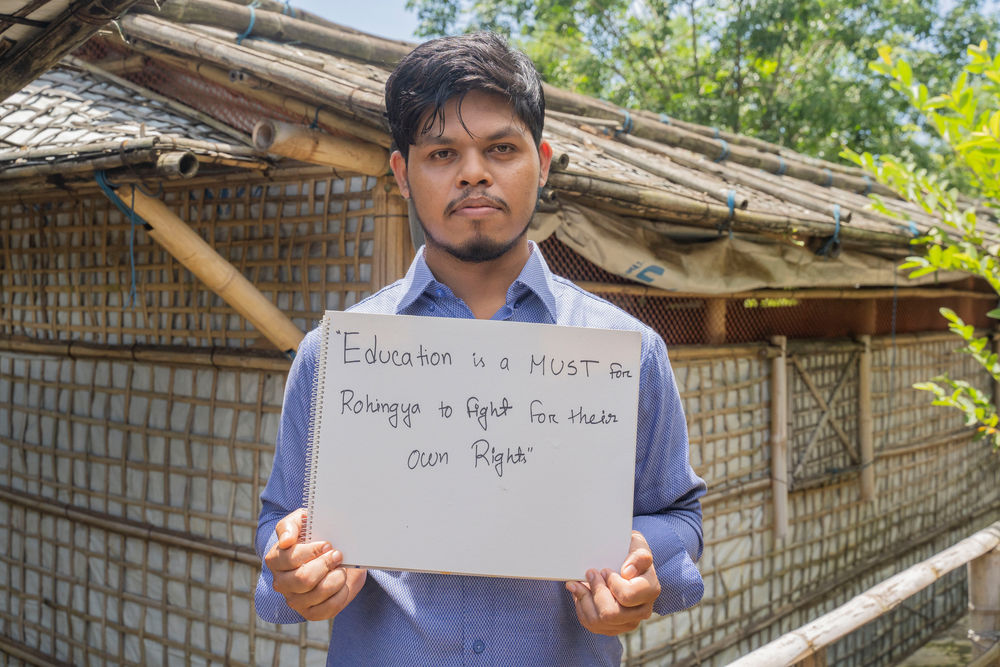

Rohingya live in many different areas, but predominantly in Bangladesh, Myanmar and Malaysia. For the Rohingya in Bangladesh, due to their statelessness and the situation they find themselves in, they're forced to live in enclosed camps. These are surrounded by barbed wire and razor fencing. They don't have the freedom o move outside or even inside the camps, which a policy that's enforced by police and military checkpoints. They have limited access to healthcare, work opportunities and education.

The lack of legal status in a country like Malaysia means they can't get a proper education. They can't have legal jobs and as a result of that, many end up in carrying out what people call “3D” jobs - dangerous, difficult and dirty jobs. In Myanmar, as a lack of their status and rights, they face serious restrictions when accessing any type of basic service. So that's healthcare, education and livelihood.

The lack of this legal status and inability to be provided with any type of protection means that stateless people and especially the Rohingya, are exceptionally vulnerable to exploitation and abuse including trafficking, violence, sexual violence, forced labour, and arbitrary detention.

Imagine yourself in a situation of extreme vulnerability where you should be able to study but you can't, where you should be able to live your life and move around freely, but you cannot, where you should be able to vote, where you should be able to participate in elections and raise your voice in parliament, but you cannot. When all your rights have been taken away. As one Rohingya has phrased it: “We are nothing but a walking corpse. The world is made for everyone to live. Today we have no country of our own, despite being human.”

Rohingya, as they articulate, often feel less than human. One 65-year-old man said: “I’m asking the world—I'm saying to the world, we are just as human as you. We are requesting the world to help us live as humans. My wish is to have rights and peace.”

HOW DO PEOPLE BECOME STATELESS?

People can be born stateless or they can become stateless. In some circumstances, discrimination against certain minority groups can be the cause, and this is the case with Rohingya. The Rohingya are a Muslim minority group from Rakhine State, Myanmar. They are also effectively the largest stateless population in the world, and this is due to restrictive provisions and applications of a 1982 Myanmar citizenship law. This law basically links citizenship to the membership of 135 national races—of which Rohingya are not considered to be a part.

Rohingya in Myanmar were stripped of their citizenship and because of this they continue to suffer entrenched discrimination both in law and in practice. They're denied fundamental rights. They're segregated, confined to camps and villages. They're cut off from access to adequate food, healthcare, education and their livelihoods. And they suffer persecution.

The Rohingya live through a constant cycle of fear. They're subjected to violence by military that includes murder, torture, sexual violence, destruction of property, and burning of their villages. In many cases, entire villages have been burnt to the ground. As a result of this violence and persecution, Rohingya have been forced into displacement throughout Rakhine State, but also across borders to Bangladesh.

WHAT IS THE HISTORY OF STATELESSNESS?

Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says everybody has a right to a nationality. There are also two important treaties: the 1954 convention relating to the State of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. Unfortunately, many countries including those where the Rohingya live including Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Malaysia have not signed up to these treaties.

It's not only Rohingya people who are stateless, but they are the largest stateless population in the world today. There are other stateless persons in a number of different countries, including Burkina Faso, Mali, Ghana, Thailand, Iraq, Kuwait and there are several stateless people throughout Europe.

DO ROHINGYA PEOPLE CONSIDER THEMSELVES STATELESS?

While I can't speak on behalf of the entire Rohingya population, of course, Rohingya consider themselves to be stripped of their citizenship in their homeland, which is Myanmar, they have a deep-rooted connection and belonging to their home where they come from.

It's become more of a legal term but calling the Rohingya stateless can legitimise what the Myanmar government has actually done. So, in legality, yes, the Rohingya are stateless, but in reality, they belong to their homeland, connected by generations of those who have lived there.

The Rohingya have been denied nationality now for 40 years and this is because of this discriminatory Myanmar's citizenship laws.

This year marks five years since the most recent campaign of violence unleashed by the Myanmar military against the Rohingya in Rakhine State, which forcibly displaced over 700,000 refugees to Cox's Bazar in Bangladesh over the course of a few months. Conditions remain dire in those camps and within Rakhine and within Myanmar.

Even though there has been an increase in awareness around the flight of Rohingya and it has been raised over the last five years, they still remain displaced, persecuted, extremely vulnerable to exploitation and with essentially no one to protect them and nowhere to go.

Durable, long-term solutions, including a permanent resettlement plan, are needed to enable the Rohingya people can live, like humans, with basic rights.