The migration route through central America and Mexico is long and dangerous—those who take it cross rivers, mountainous regions, and swampy terrain. It’s not just adults that risk this dangerous journey, children of all ages are also forced to flee their homes in search of safety or a better life. Some children are with their families—often having left home without much or any explanation—others travel alone. They all face a future of uncertainty.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provides mental health care to children and adolescents on the move at various points along the migration route in Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico. Many of them report experiencing or witnessing violence, discrimination, and trauma. Poor physical and mental health is particularly worrying among children and adolescents as it can impact their development and their general well-being.

I´m afraid, I don’t like to be in a place like this because my brother, my mom and me were kidnapped for three months

- 8-year-old Pedro

How do children perceive migration?

Generally, children don´t receive any explanation about the events that happened to them before they left home or along the migration route. People think that because they are young, they don’t understand that something bad has happened, and therefore don’t need an explanation. And because they don’t have the necessary tools to understand and manage the emotions they are feeling, they express those emotions through their behavior.

“Many times, when the children are with me, [they exhibit] some bad behaviors associated to their experiences,” said Esther Huerta, community advisor at the Comprehensive Care Centre in Mexico City. “For example, violence. Not because they want to [harm] others, but because that´s what they have known, and they don´t know any other way to interact.”

MSF staff use play therapy and recreational activities to help children name their emotions, talk about them, redirect them, and manage them. These techniques also help our teams understand the emotional state of a child so that they can then provide appropriate psychological care.

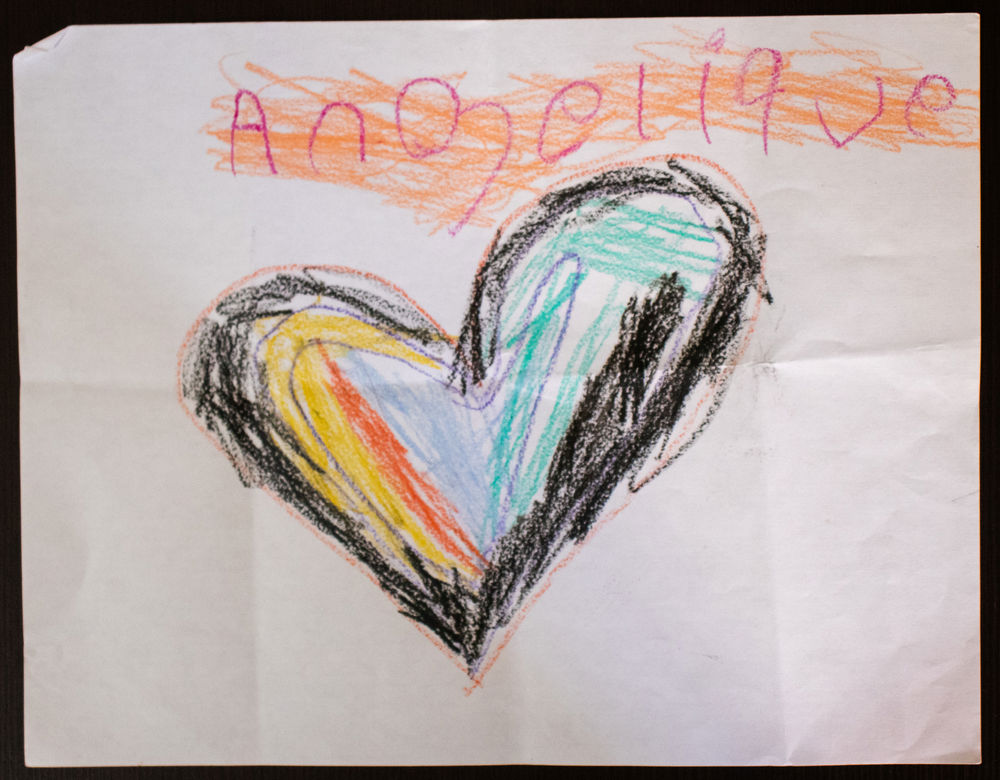

One of the activities is called “How is your heart?”. Where children name emotions, draw a heart and color it in according to how they have felt that week or that day.

“The emotions that are generally predominant are: ‘anger’ because they are tired of waiting; ‘sadness’ from being away from their country; and ‘fear’ of not knowing what will happen to them,” said Lourdes Ceballos an MSF health promotion supervisor who works in our project in Reynosa, northern Mexico along the US border.

Example of “How is your hearth?”

Example of “How is your hearth?”

Another technique used to redirect the emotional burden children carry is with Worry Dolls, a Mayan tradition from Guatemala. Children are invited to tell the dolls about their fears and worries, which are then absorbed by the dolls during the night. The next day all the children’s worries will have disappeared.

Worry Dolls, a Mayan tradition from Guatemala

Worry Dolls, a Mayan tradition from Guatemala

Usually, the children’s concerns are related to their responsibilities: They feel the responsibility to take care of their relatives, they are concerned for the future, or they are experiencing grief.

In spite the situation they are facing, these children keep looking for ways to adapt. “Many of the children have created strong support networks and take care of and teach each other,” said Ceballos. “In addition, due the economic constraints they face, they have learned to monetize what they have. For example, if we teach them how to make bracelets, they learn, improve, and sell them. They know that with this income they may be able to buy a candy or help their parents.”

They also have hope that one day they will get to a ‘better place’, where they will be able to study, have a safe home and see their relatives happy and carefree. “They often say, ‘When I go to the USA’, or ‘the day we are called’,” said Ceballos. “I guess this helps them [have hope]. There is no plan B in their minds.”

MSF provides medical and psychological care, psychosocial counseling, and health promotion activities at various locations along the migration route in Central America and Mexico—in Trojes and Choluteca in Honduras, San Marcos and Huehuetenango departments in Guatemala, and Tapachula, Tenosique, Salto de Agua, Palenque, Coatzacoalcos, Ciudad de Mexico, Ciudad Acuña, Nuevo Laredo, Piedras Negras, Reynosa and Matamoros in Mexico.