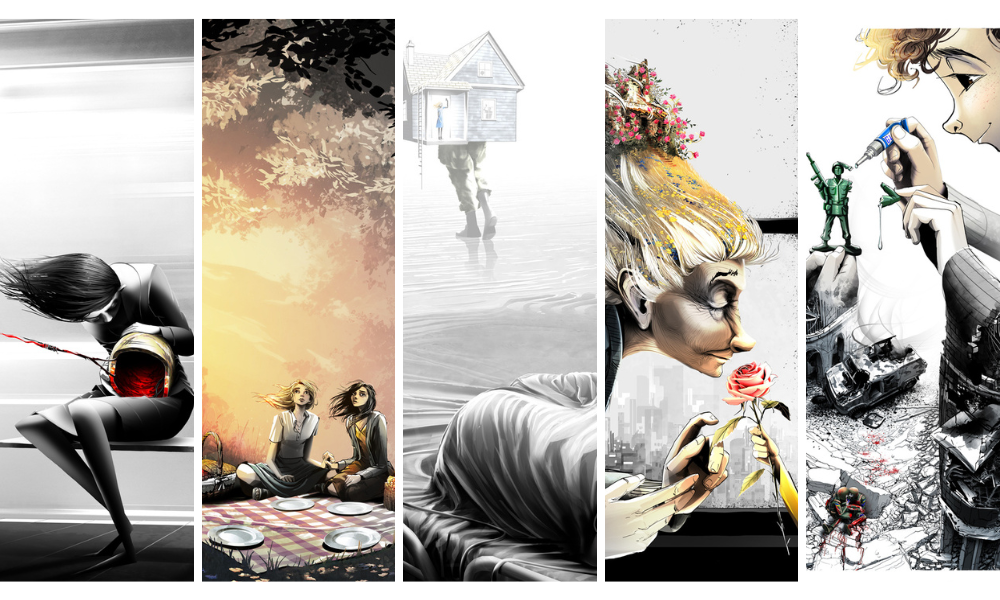

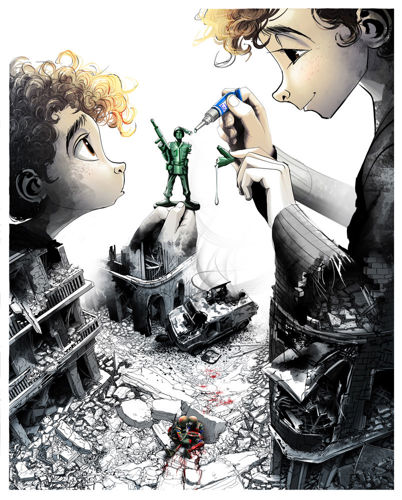

We invited Ella Baron, an illustrator based in the United Kingdom, to visit our projects in Vinnytsia and Cherkasy so that she could use drawings to capture things that are, as she says, “beyond a camera’s reach”. Below are testimonies and their accompanying illustrations, taken in May this year and shared by Ella Baron.

When Dima, 20, regained consciousness in hospital, he phoned his mother to tell her that “everything was fine — just a few scratches'. It wasn’t true. “There was a big hole in my leg, my ear, and my arm.” He still can’t sleep: “My nightmares are always the same. They take me from the hospital back to the trenches, and then I’m above it all. I’m the drone making the projectile drop that hits me.” Dima flies FPV drones, so he knows what this looks like.

The shard of shrapnel that buried itself in Dima’s body when the drone projectile detonated is now sitting on his bedside table. He tells me that it “momentarily paralysed me from the bottom of my spine to the ends of my limbs. I thought it had injured my spinal cord and that I wouldn’t be able to walk. I thought, this is the end. But I started to touch my head to see if there was any blood. When I didn’t find any, I said to myself, ‘I am alive; I am not dead.’ I could hear enemy drones overhead. FPVs have a horrible, squeaky sound, like Formula 1 cars. If it's high, it's quiet. But when it gets louder, you start to worry. I could hear them, so I lay very still and pretended to be dead. I heard them leave, thinking I was dead. Then I started screaming from the pain. I thought I was going to bleed to death.”

He tells me that he survived because he is his mother’s only child. “When I joined the army, she cried, so I promised her that everything would be fine. His mother is a kindergarten teacher and the kindest person in the world.

In 2022, Roman, 40, quit his job as a parcel collector and joined a medical brigade to collect injured and dead soldiers. He says that “sometimes the body parts were blown up into the trees”. When the drone detonated, his legs didn’t get that far. They ended up in the box next to him at the medical stabilisation centre, still in their shoes. He recalls, “I remember looking at my legs in the box, separate from me. I was so scared when I realised that I couldn’t get this part of my past back, that my future would be very different. I was so sad to say goodbye to what was in the box... Then I realised that it was too early for me to die. I hadn’t said goodbye to my family or finished building the house for them.”

When Roman started building the house almost twenty years ago, he went to the bank to take out a loan from a very beautiful woman with white-blonde hair. “I told her all about the house, and she said, 'Maybe one day you’ll show me.' I took her number and invited her for coffee.” Roman and Tania married soon after and now have two children: Oleksii, who is 12, and Ivan, who is 21. Their house is finally almost finished – white pillars and blue walls – with only a few tiles on the roof left to complete, and maybe a swimming pool too. Roman tells me how his family loved to go swimming in the sea in Odesa. “We used to go all together, but if I imagine going back, there's one thing I can't understand: how will I be able to go in the sea? Can you swim with a prosthesis?” I don't know the answer to that, but after a long pause, Roman does: “My eldest son Ivan goes to the gym. His muscles are even bigger than mine. He can carry me on his back into the sea. I'll swim with him. Then he’ll take me back out of the water, put me on the chair, and I’ll put my prosthesis back on. That’s how it will be.”

Roman says he called his wife from the hospital to tell her that he’d lost his legs, but to not worry as everything is fine and nothing has changed. “I don’t want anything to change.”

Inna, 42, and Tetiana, 48, have both been separated from their loved ones by the war. Tetiana’s son, Valerii, and Inna’s husband, Mykola, are both prisoners of war in Russia. They were both captured on the same day in May 2022. Valerii is 27 now. Inna struggles to remember her husband’s age. She says it’s because “we don’t celebrate birthdays anymore. When they were captured, everything stopped.”

Inna and Tetiana wait at every prisoner exchange in the hope that their relatives will be among those released. If they aren’t, sometimes the soldiers who are brought back bring news of them. For the first year of her husband’s captivity, Inna struggled to eat. She says she’s a bit better now because she’s found Tetiana: “We have the same pain; we understand it.” Both women believe they have a 'spiritual connection' with their loved ones and that they must 'stay strong and cry less so they may also feel our hope and prayers'. Inna describes how her husband visits her in her dreams to check on her.

She tells me that she likes to picture herself sitting with her husband in their garden in Mariupol. Mykola liked to grow flowers there — wild forest flowers. “I don’t even know where he got those seeds! At the time, I didn’t even like them! But now, nothing would make me happier.” Tetiana says she also likes to picture Valerii 'somewhere in nature, in a field of white chamomile with the sun shining brightly, surrounded by birdsong and fresh air'.

Neither Inna nor Tetiana has had any direct contact with their relatives for three years. If they could talk, Inna tells me, she would say, “I love him — we're waiting.” “We're definitely going to wait,” adds Tetiana.

Petro, 40, says he and his older brother, Dmytro, 43, have been “making little models of soldiers together since childhood, and conducting fake wars. Then we grew up and had a different kind of war.” Dmytro says that “in the war, we were always together”. They were together when the drone detonated under their car, killing the other two soldiers with them. The brothers are now recuperating from their injuries in the same hospital, in different wards, but each brother tells their stories mostly about the other.

Petro says that when the drone detonated, “I felt a very strong burning sensation and I was screaming. My brother was screaming that he was injured too and I was so happy that he was screaming because it meant he was alive.” Dmytro says: “I heard my brother’s voice and I calmed down. It probably all happened very quickly, but it felt like time stopped. When I realised that Petro was seriously injured in all four limbs – how much blood he was losing – I knew that I had to provide medical aid for him or he would die. I’ve been on the frontline for a long time. I’ve tied a lot of tourniquets. So in this situation I’m not panicking. I’m calm. I tied the tourniquets. But I was worried about him.” Petro says Dmytro worries too much, “but it’s natural, I’m his little brother.” Dmytro says: “I’ve been protective of Petro since picking him up from kindergarten. He’s not weak, he’s very strong. But I have to look after him. He’s my little brother.”

They are now healing well, although Dmytro says he’s worried about Petro’s hands. His doctors say he’ll never regain full movement. Dmytro says his brother has “golden hands: whatever he likes to do with them, he does so well. He’s very creative: a sculptor, he plays the guitar.” Petro says it was Dmytro’s guitar – his brother bought it but got bored after learning one song and quit, so Petro learned to play instead.

Petro hopes the war has left him with enough movement in his hands to go back to making sculptures, and there’s one sitting on his bedside table in the hospital. It’s a phone stand with the insignia of his village’s brigade, which he insists on giving to me. I’m concerned that without it Petro won’t be able to hold his phone, as one hand is swathed in bandages and the other sutured to his midriff. Petro spends a lot of his time on his phone, mostly video calling Dmytro in the hospital ward downstairs.

Natalii is part of a women’s support group in Vinnytsia for refugees from Hierson. Today, they’re making flowers out of colourful pipe cleaners. The windows of the community room are filled with flowers that Natallii grows in little recycled pots. She talks about her garden, back in Hierson, where she lived before the invasion. 200 sq metres filled with apricot trees and grape vines and flowers; her favourite were the pink roses. Recent photos taken by a friend who stayed behind show that their house has been utterly destroyed - but the roses in the garden are still blooming.

Now Natalii lives with her family in a small apartment in Vinnytsia, ‘there’s no garden but a good window. For my birthday I was given a huge bouquet, and there were still some roots! Now I have seven big bushes in water on the floor in front of the window.’ She says her family think she’s mad, apart from her 9 year old grand daughter, Anya- who also has green fingers. Anya’s father, Natalii’s son, always buys her flowers from the supermarket when he comes back from the front.

‘The flowers are like a memory from home…peace is the memory of the life that we were living there. Here, we are just waiting… my soul is in the garden back home in Herson. ’ Natalii added.

As Natalii, talks the other women have been twisting their pipe cleaners into flower ornaments. Svitlana, 68 and also a refugee from Hierson, has hands that tremble so violently that Natalii helps her with the fiddly bits. When told about this project she says, ‘ no picture could capture what we have lived through, what it is to have everything, to be together with all your family in your home, and then be living by the side of the road.’ It’s a fair point.

Since February 2022, the full-scale war in Ukraine, has triggered a dramatic increase in the number of people in Ukraine with long-term injuries requiring complex care. This includes individuals with blast injuries, shrapnel wounds, and amputations, all of whom require intensive, specialised care, placing extra strain on the country’s health system. In response, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) launched an early rehabilitation project at Cherkasy Hospital in central Ukraine in March 2023. This project provides physiotherapy, psychological support and nursing care to address the complex needs of patients wounded in the war early in their recovery process.

Mental health is also central to the care that MSF provides in Ukraine. In 2023, MSF began offering specialised psychotherapeutic services to people showing symptoms of war-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Vinnytsia. A custom-designed mental health centre opened in September 2024. In this centre, MSF offers one-to-one psychological sessions, also sessions for members of patients' support networks, and provide patients with techniques to help reduce symptoms, increase coping skills and decrease the consequences of traumatic stress.

In addition, our Vinnytsia team also provides evidence-based treatments for war veterans who have been wounded or demobilised and are readjusting to civilian life, as well as for their relatives and families, and for displaced people affected by the war. The centre uses therapies such as Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) to help patients process traumatic memories and alleviate PTSD symptoms.